The Clean & Prosperous Institute Study Mission delegation that visited Québec City and Montréal flew from Seattle on traditional, “unsustainable” aviation fuel – though the Institute did buy carbon offsets. Will future study mission delegations fly on commercial jets powered by sustainable aviation fuel (SAF)?

To help answer that question, we learned about advances in SAF from a briefing by Jean Paquin, President and CEO of the SAF+ Consortium, and a tour of the SAF+ Consortium’s pilot plant.

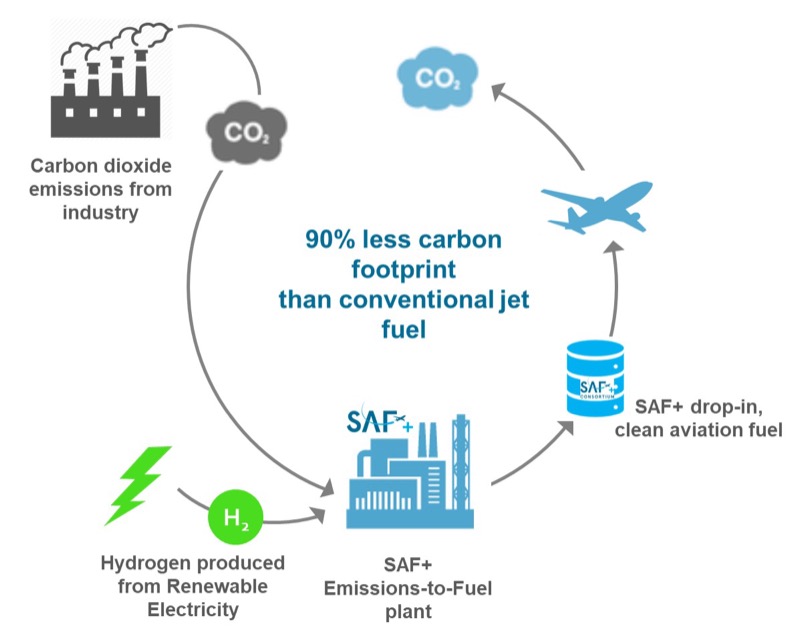

But first, what is SAF? It’s a greener alternative to traditional, refined-from-oil jet fuel. It can be produced from fats, oils and greases, or from biomass such as algae, municipal solid waste, or agricultural and forest residue. eSAF is produced with a Power-to-Liquid (PtL) process of electrolysis that extracts hydrogen from water, and carbon from atmospheric carbon dioxide or from industrial waste gas, using renewable electricity. This PtL process is what the delegation saw at the SAF+ Consortium’s pilot plant in Montreal.

Per GreenBiz,

SAF’s great advantage is that it’s a “drop-in” fuel — you can pump it straight into aircraft fuel tanks without expensive retrofitting to aircraft or special infrastructure at airports. Current regulations only permit commercial aircraft to use a 50/50 mix of SAF and regular kerosene. But in March, Airbus successfully tested its A380 — the world’s largest passenger aircraft — with one of its four engines using 100 percent SAF. Airbus has conducted similar tests on other aircraft models and on a helicopter. In June, a Swedish regional airline completed the world’s first test flight with a commercial aircraft flying SAF in both its engines.

So much for the good news. The bad news is that SAF is still very expensive — anything between two and five times the 2019 price of conventional jet fuel. As a result, SAF represents less than 0.1 percent of global aviation fuel consumption today — a tiny step that needs to become a giant leap.

That giant leap will depend on supply going up and cost coming down. Already, even with cost at an early-stage premium, there is growing demand for SAF. Delegation participant Charles Knutson of Amazon noted that his company is the world’s largest cargo buyer of SAF.

That giant leap will depend on supply going up and cost coming down. Already, even with cost at an early-stage premium, there is growing demand for SAF. Delegation participant Charles Knutson of Amazon noted that his company is the world’s largest cargo buyer of SAF.

Boeing has agreements to purchase 5.6 million gallons of blended SAF produced by Neste – the world’s leading SAF producer and another delegation participant – to support its U.S. commercial operations through 2023. These agreements more than double the company’s SAF procurement from last year.

In May, United Airlines was the first carrier to sign an offtake agreement with an overseas supplier (again, Neste) for 50 million gallons of SAF for its flights out of Amsterdam. This is on top of the long-term agreements already signed by major US and European carriers to purchase half a billion gallons of SAF. United estimates that it currently buys nearly half of all available SAF.

In May, United Airlines was the first carrier to sign an offtake agreement with an overseas supplier (again, Neste) for 50 million gallons of SAF for its flights out of Amsterdam. This is on top of the long-term agreements already signed by major US and European carriers to purchase half a billion gallons of SAF. United estimates that it currently buys nearly half of all available SAF.

United is not only buying SAF, but also investing in production via a joint venture known as Blue Blade Energy. United Airlines has signed an offtake agreement with Blue Blade Energy for up to 135 million gallons of the future ethanol-based SAF annually and up to 2.7 billion gallons in total. This corresponds to 50,000 flights powered by unblended SAF between United’s hubs in Chicago and Denver per year. Blue Blade’s new SAF technology was developed by researchers at the US Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL), a leading center for technological innovation in sustainable energy in Richland, WA.

cCarbon reports that “the Sustainable Aviation Fuel market size stood at US$1.1 billion in 2022, up from US$50 million in 2019 registering an annually compounded growth rate of 115.38%. As per cCarbon estimates, the market is expected to reach a value of US$29.7 billion by 2030.”

cCarbon reports that “the Sustainable Aviation Fuel market size stood at US$1.1 billion in 2022, up from US$50 million in 2019 registering an annually compounded growth rate of 115.38%. As per cCarbon estimates, the market is expected to reach a value of US$29.7 billion by 2030.”

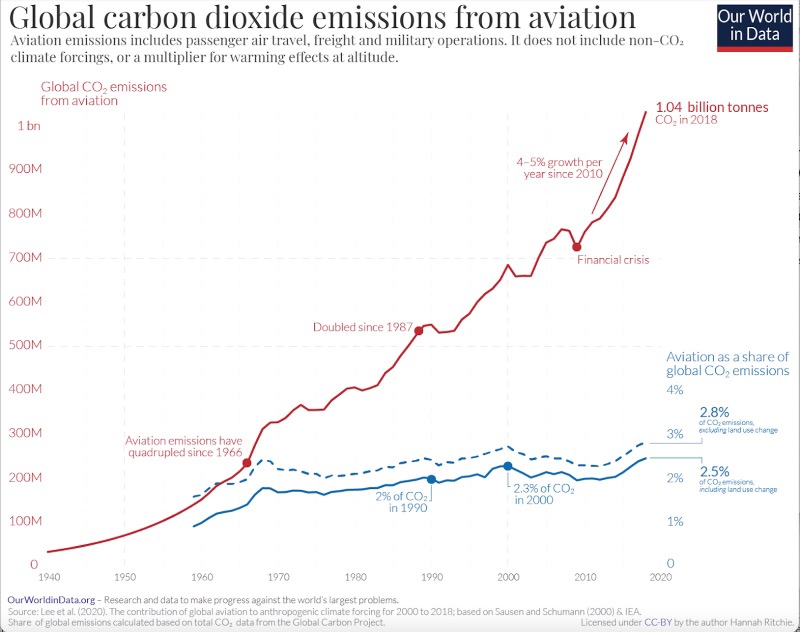

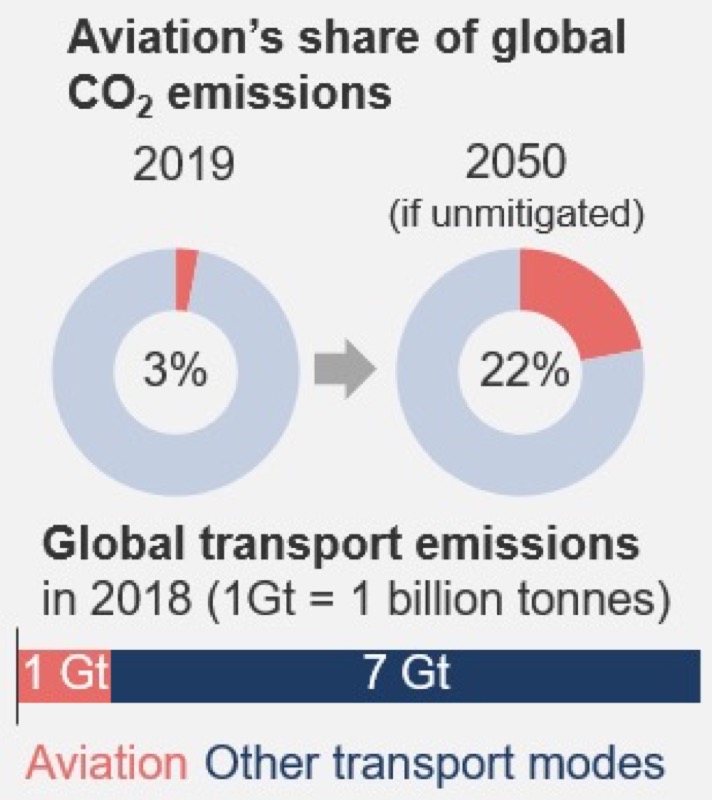

Québec’s SAF+ Consortium intends to be a major player in this growing market. During his briefing to the Clean & Prosperous Institute delegation, Jean Paquin noted that while the aviation sector’s share of global greenhouse gas emissions is relatively small now, as other sectors decarbonize aviation’s share will expand to over 20% by 2050.

Source: Climate change and flying: what share of global CO2 emissions come from aviation

That is, unless the airline industry pivots to SAF, including Paquin’s “Pollution-to-solution” technology:

Graphic from SAF+ Consortium safplusconsortium.com

Graphic from SAF+ Consortium safplusconsortium.com

For more about how SAF+ is made, watch this 2½-minute video:

We got a first-hand look at SAF production on our Study Mission tour of the SAF+ plant. And at the end of our tour, we were presented with a growler of SAF fuel.

Shortly after our tour, the Consortium attended the Paris Air Show where they announced that beginning in 2030 they’ll supply SAF to the Air France-KLM Group.

While Québec works to develop its sustainable aviation fuel supply chain, Washington state – led by several of the government and business leaders in the delegation – works to leverage its abundance of aerospace innovation, clean energy, and sustainable feedstocks toward a leadership position in the emerging SAF industry.

Washington state offers a per-gallon SAF Business & Occupation tax credit, thanks to Representative Andy Billig’s WA SB 5447/HB1505. Qualifying fuel will receive $1 per gallon plus $0.02 for each additional 1% reduction beyond 50%, capped at $2. “Our state is already at the forefront of the aviation industry, and we should also be a leader in the development of cleaner fuels for those same airplanes,” said Billig in a statement. “This is a market just waiting to be tapped. There are potentially hundreds of family wage jobs and wonderful opportunities for businesses in this emerging industry, and we’re just now scratching the surface.” The legislation will implement key recommendations from the Washington State University Sustainable Aviation Biofuels Work Group December 2022 Final Report.

In Washington, D.C., the U.S. Department of Energy is leading a government-wide strategy for scaling up new technologies to produce SAF, with a goal of meeting 100% of domestic aviation fuel demand with sustainable fuel by 2050. That initiative aims to boost SAF production to at least 3 billion gallons/year by 2030 and wean the sector off petroleum-based jet fuel completely by producing 35 billion gallons/year of SAF by 2050. According to Secretary Jennifer Granholm, “Not only is Sustainable Aviation Fuel critical to decarbonizing the airline industry and reaching our climate goals, but this plan will help American companies corner the market on a valuable emerging industry.” The Department of Energy is supporting SAF development with IRA-funded grants and tax incentives.

With federal and state government assistance, Washington state SAF producers are making headlines.

From Fast Company:

A startup called Twelve is building the U.S.’s first large-scale factory to make jet fuel from CO2 in Washington state. By next year, Alaska Airlines plans to buy the fuel.

On the site of a former sugar beet mill in Moses Lake, Washington, a startup called Twelve is building a very different type of factory: one of the first to make jet fuel from CO2 and renewable electricity.

From The Seattle Times:

New $800M sustainable aviation fuel plant planned for Washington state.

Dutch company SkyNRG has chosen Washington state to locate a major new biogas plant that will produce sustainable aviation fuel — a key part of the airline world’s push to decarbonize flying.

From WSUTC News:

Washington State University Tri-Cities and Snohomish County will partner to bring a proposed research and development center for sustainable aviation fuels to life.

Snohomish County officials announced Tuesday plans for a $6.5 million Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) Applied Research and Development Center located at Paine Field in Snohomish County. The first-of-its-kind center will offer fuel testing, fuel finishing and the world’s first fuel repository.

From The Northern Light:

BP planning for $1.5 billion green investment at Cherry Point.

BP’s Cherry Point Refinery could be subject to a $1.5 billion investment that would make the Whatcom County facility a future hub for green energy.

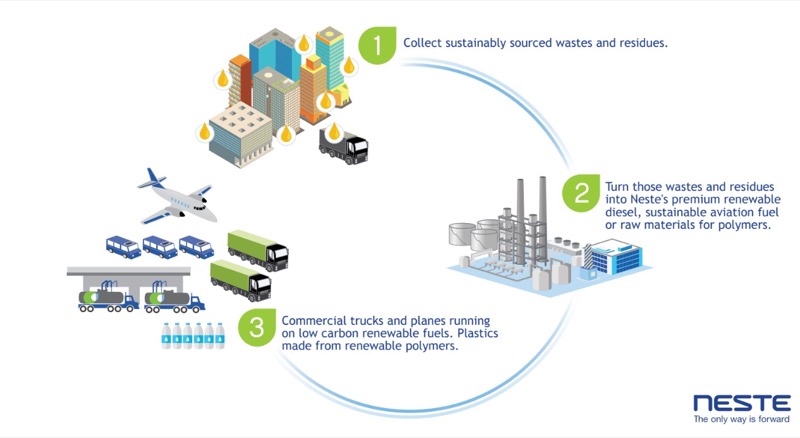

Because Neste is the world’s largest producer of SAF, we were pleased to have them join the Study Mission as a sponsor. Neste’s Ender Reed told us that they “spend a lot of money on research and development [looking at] future feedstock opportunities – whether it’s municipal waste, whether you’re talking about algae, and very importantly here in Québec a great lignocellulosic forestry waste opportunity.” (We have plenty of all three of those feedstocks here in Washington, too.)

So… Will future study mission delegations fly on commercial jets powered by sustainable aviation fuel? Almost certainly. And maybe… on a Boom Supersonic!